Then: 11/10/2021

musing

William Morris on Textile Fabrics

by Vestoj Editors

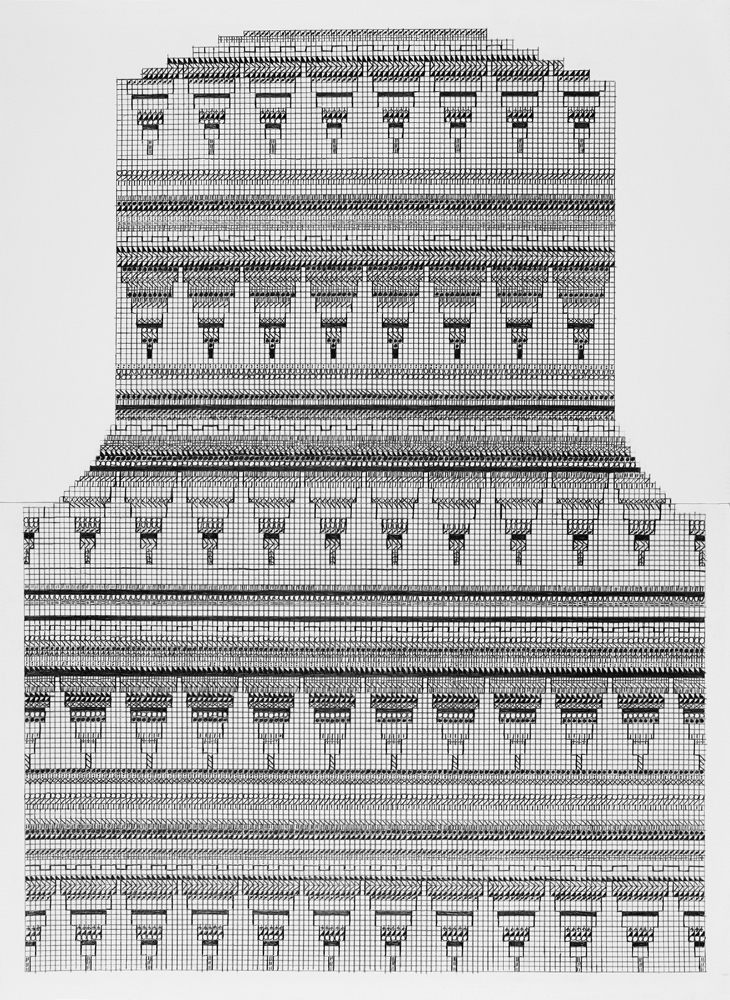

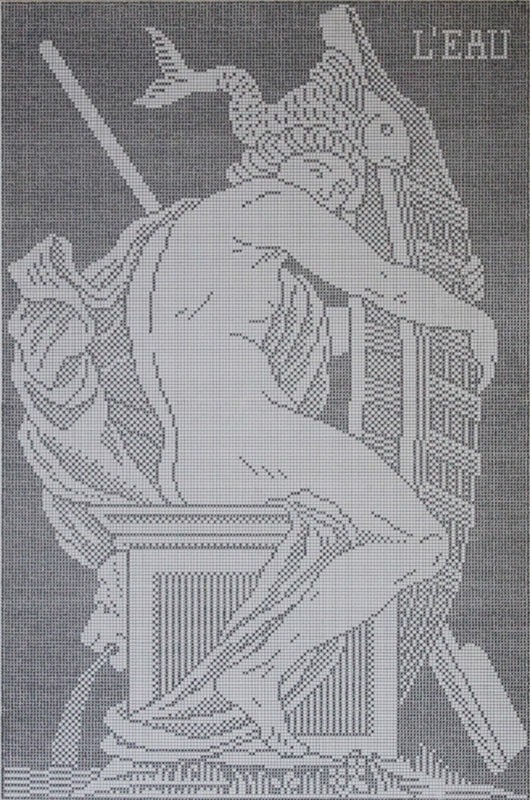

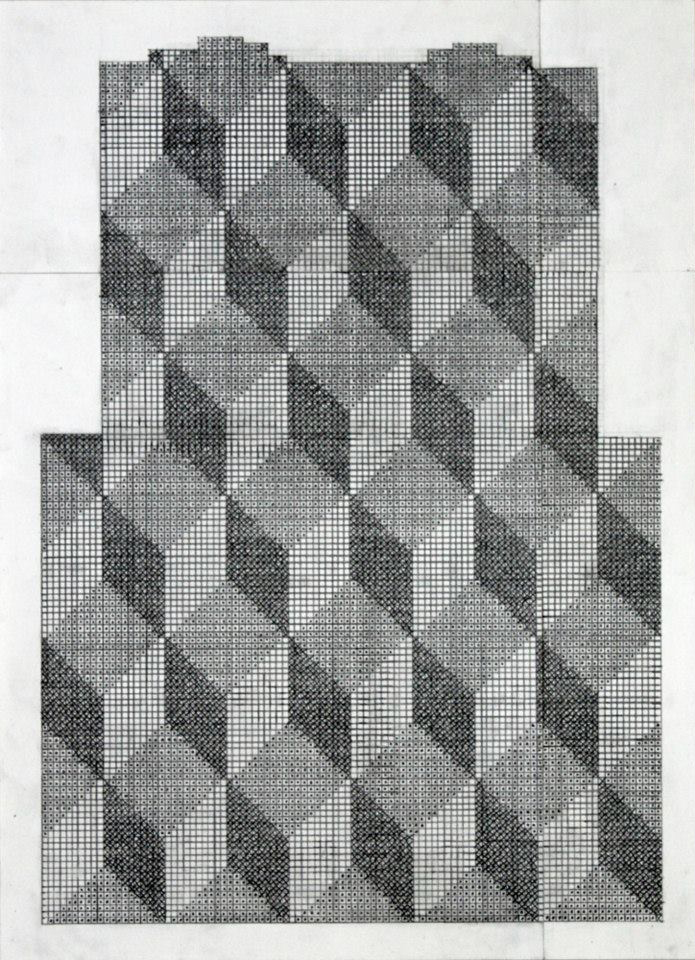

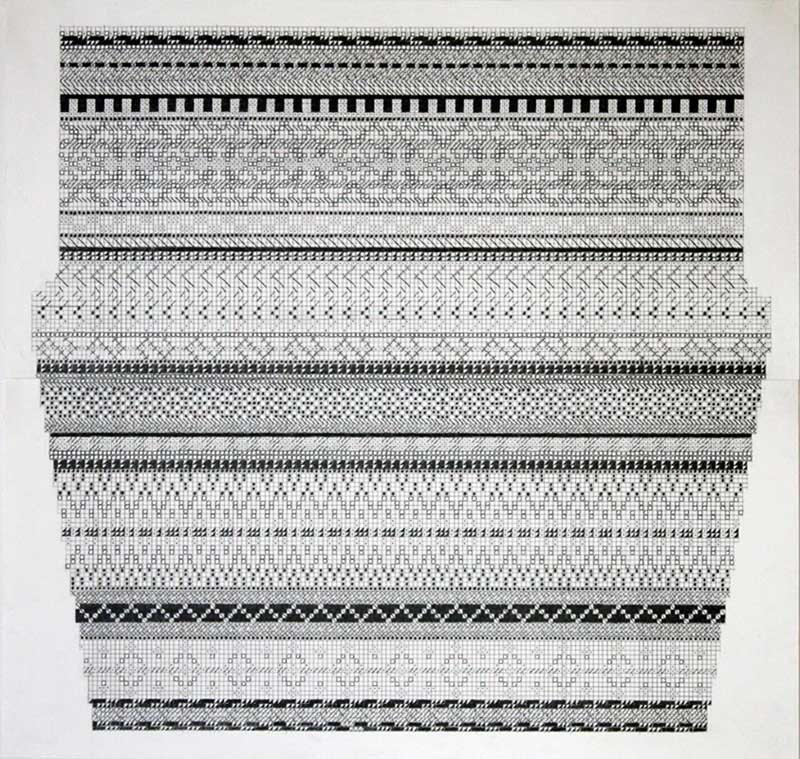

Graphite illustrations by Robert Otto Epstein

Keywords: Arts & crafts movement, Damsel-peopled castles, Ornamented cloth, Warp & weft

IN A LECTURE DELIVERED to the International Health Exhibition at the South Kensington Museum, London in 1884, William Morris gives a detailed history on textiles – weaving, tapestry and dyeing – and the textile industry. His talk traces the lineage of textile craft, spanning Classical Greek decoration, Byzantine ornament, Medieval textiles, Italian silk of the fourteenth century, to Morris’ contemporary time of the late nineteenth century. Morris, a textile designer himself, as well as a poet and essayist, was prominent spokesperson of the arts and crafts movement which occurred in the United Kingdom and spread to Europe and North America from 1880 to 1910. Morris argued for the unification of design and production processes in making decorative items, reacting against the state of the textile and design industry which had, at the time, become a severely mechanised process, no longer made by hand.

An excerpt of the lecture by Morris is the subject I have to speak on is a sufficiently wide one, and I can do little more than hint at points of interest in it for your further thought and consideration; all the more as I think I shall be right in supposing that, except for anyone actually engaged in the manufacture of textiles who may be present, you, in common with most educated people at the present day, have very little idea as to how a piece of cloth is made, and not much as to the characteristic differences between the manufactures of diverse periods. However, one limitation to my subject I will at once state: I am going to treat it as an artist and archaeologist, not as a manufacturer, as we call it; that is, I shall be considering the wares in question from the point of view of their usefulness (using the work in its widest sense) to the consumer, and not as marketable articles, as subject-matter for exchange. I must assume that the goods I am speaking of were made primarily for use, and only secondarily for sale; that, you see, will limit me to a historical discourse on textile fabrics, since at present those wares, like all other wares of civilized countries, are made primarily for sale, and only secondarily for use.aired with the graphite drawings by artist Robert Otto Epstein. Epstein’s works are realised through a process of drawing on to hand gridded paper and marked square, filling in the pattern with a pencil, square by square.

The subject I have to speak on is a sufficiently wide one, and I can do little more than hint at points of interest in it for your further thought and consideration; all the more as I think I shall be right in supposing that, except for anyone actually engaged in the manufacture of textiles who may be present, you, in common with most educated people at the present day, have very little idea as to how a piece of cloth is made, and not much as to the characteristic differences between the manufactures of diverse periods. However, one limitation to my subject I will at once state: I am going to treat it as an artist and archaeologist, not as a manufacturer, as we call it; that is, I shall be considering the wares in question from the point of view of their usefulness (using the work in its widest sense) to the consumer, and not as marketable articles, as subject-matter for exchange. I must assume that the goods I am speaking of were made primarily for use, and only secondarily for sale; that, you see, will limit me to a historical discourse on textile fabrics, since at present those wares, like all other wares of civilized countries, are made primarily for sale, and only secondarily for use.

As to the kinds of weaving: first there is plain weaving in its simplest form, where the weft crosses the warp regularly and alternately. Of that I need say no more, because I have to speak mostly of the characteristic ornament of the different periods, and this plain weaving is not susceptible of ornament, woven ornament I mean. To obtain that the weft must cross the warp at regular intervals, but not alternately; on the surface either warp or weft must predominate to make a pattern.

Sometimes, as a subdivision of this common figure-weaving, the warp comes chiefly to the surface, which makes a satin; and also sometimes these warp threads are caught up over wires with a sharp edge, which are pulled out as the work goes on, leaving a surface with a raised pile, that is velvet. In the next kind of weaving the weft crosses the warp alternately indeed, as in plain unpatterned weaving, but instead of being carried in one stroke all across the web, ends or returns wherever the colour changes, so forming a kind of mosaic of coloured patches; this is tapestry, using the word in its narrowest sense. As a detail of this work I ought to mention that in tapestry-weaving the weft is put in so loosely, driven home so carefully, that the warp is entirely hidden by the weft. That work may be considered as a sub-division of this kind of weaving, where thrums of wool, hair, or silk are knotted into a plain canvas as the work proceeds, so as to form a pile with their cut ends; this is carpet-weaving. Lastly comes a kind of ornamental web, in which the ornament is not produced by weaving, but by painting by hand or printing combined in various ways with dyeing in the piece; we call these printed goods chintzes and so on. Needle-worked embroidery is another way of ornamenting a cloth; but I shall not deal with this form of ornamented cloth.

Let us consider briefly the practical history of these three arts; and first the mechanical or common weaving. With wares so perishable as woven cloth, it is not wonderful that we have little read record of the stuffs of antiquity; because the descriptions of the poets and writers of the time cannot be depended on for accuracy, as they of course assumed a general knowledge in their audience of the articles described. The vase-painting and sculpture of the central Greek period give us at all events some idea of the quality of the stuffs worn at the period, and in so doing fully confirm the beautiful and simple description of the fine garment in the Odyssey, which is likened to the inner skin of an onion: a figure of speech which, taken with the representations of delicate cloth in the figure-work of the time of Pericles, and earlier and later, gives one an idea of something like those mixed fabrics of silk and cotton which are still made in Greece and Anatolia. Only you must remember that the early classical peoples at least did not know of either silk or cotton, so that flax was probably the material of these fine garments; and we know by the evidence of the Egyptian tombs that linen was woven there of the utmost delicacy and fineness. I don’t suppose we need doubt that mechanical pattern-weaving was practised by the Greeks in their earlier and palmy days, but only, I fancy, for the simpler kinds of patterns in piece goods, diapers, and so forth. I conclude the running borders to have been needle-work, or maybe dye-painting. We have a few representations of looms to help us in looking into this matter, which however do not prove much; they are all vertical, and at first sight look nearly like the looms used throughout the Middle Ages, and to-day at the Gobelins, for tapestry-weaving. In one which is figured on a tomb at Beni Hassan in Egypt, the details of an ordinary high-warp tapestry loom are all given accurately; but the weavers seem to be weaving nothing but plain cloth; in this loom the cloth is being worked downwards, as in the ordinary tapestry loom. In another representation, taken from a Greek vase of about 400 B.C., Penelope is seated before her famous web, which is being worked in an upright loom; there is only one beam to it, the cloth-beam, and the work is woven upward; the warps are kept at the stretch at the bottom by weights looking too small to be effective; the web is figured, [it] has a border of the ordinary subsidiary patterns of classical art, and a stripe of monsters and winged human figures. It seems to have been concluded that this represents actual tapestry-weaving, but too hastily perhaps, as the high-warp loom only means a certain amount of inconvenience in forgoing the mechanical advantages of the spring-staves worked by treadles. Also this Greek loom of 400 B.C. is in all respects like the looms in use in Iceland and the Faroes within the last sixty years for weaving ordinary cloth, plain or chequered.

continue reading at Vestoj